Joe Gutierrez Office of Strategic Communication (909) 537-5007 joeg@csusb.edu

It would be easy to watch the documentary, “Singing Our Way to Freedom,” on the life of the late Chicano musician and activist, Ramon “Chunky” Sanchez, and to raise him up as a hero.

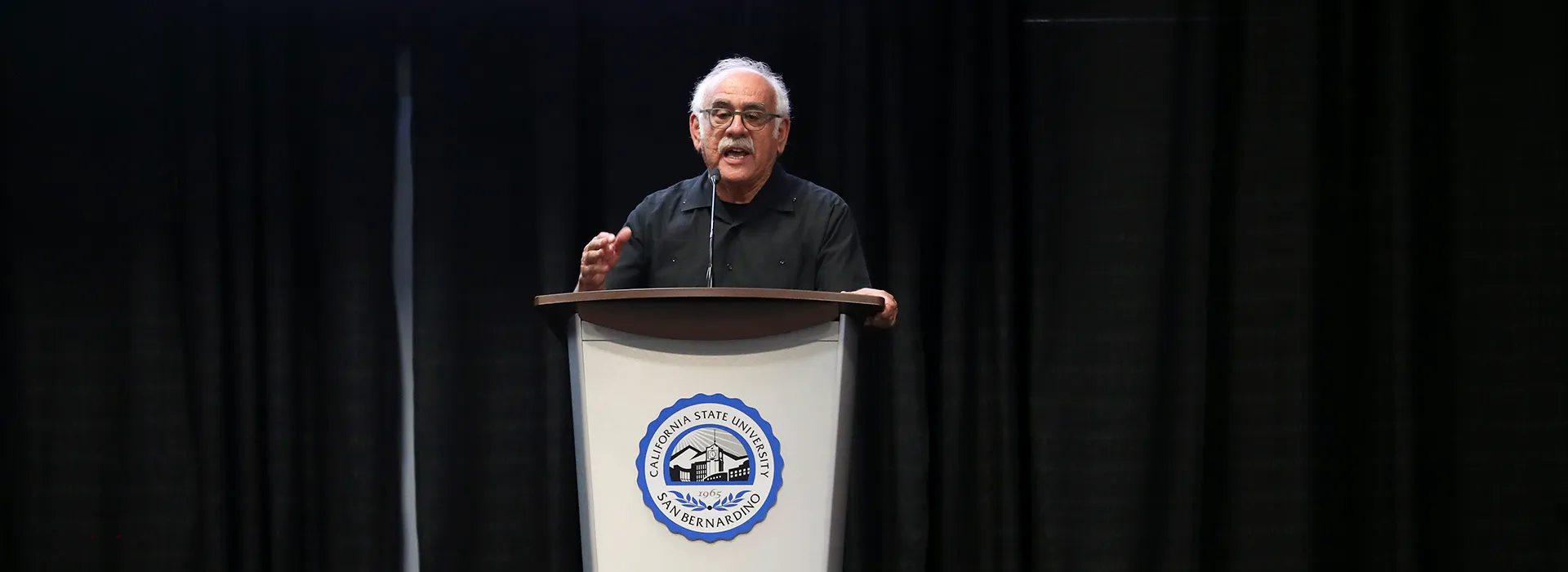

But the film’s producer and director, Paul Espinosa, said at a screening of the film at Cal State San Bernardino on Oct. 15 that Sanchez would have told people to look elsewhere.

“We have heroes all around us. One of the things about Chunky was that he was very unassuming,” Espinosa said. “I’m sure that Chunky would never consider himself a hero. And I think that’s precisely the point: There are many people who are working very hard in our community, in a lot of different realms – in the schools, teachers, artists – people in different realms doing really important work. … They are the heroes.”

The screening of the film and Espinosa’s visit was part of the university’s celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month, which ran from Sept. 15 to Oct. 15. More than 200 students, staff, faculty and community residents attended the event at the Santos Manuel Student Union Events Center.

“Singing Our Way to Freedom” focused on how Sanchez wrote and used music to help encourage and inspire people during the Chicano civil rights movement of the late 1960s into the 1970s and after.

“From the early days of the Chicano civil rights movement alongside Cesar Chavez through today’s immigrants’ rights protests, Chunky has used music to energize our political imagination in the struggle for social justice,” Espinosa Productions’ website states. “Our film examines how Chunky’s inspiring career as a musician is interwoven with the broader history of the Chicano movement, a cultural movement nearly forgotten today. A portrait of one charismatic musician and activist allows us to revisit this pivotal era in American history and to provoke dialogue about the many hurdles that had to be overcome to gain equal rights for Mexican Americans.”

The film showed how Sanchez, the son of farm workers who was born in the Riverside County desert town of Blythe on Oct. 31, 1951, became a musician, songwriter, educator and activist who was awarded the National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship Award in 2013, the nation’s highest honor presented to master folk and traditional artists. In between, he attended San Diego State, performed at rallies and marches for the United Farm Workers Union (he was said to be labor leader Cesar Chavez’s favorite musician), helped organize the effort to build San Diego’s iconic Chicano Park, and worked with gang members in San Diego to move on from that lifestyle.

Before the film was shown, Espinosa said that when Sanchez arrived at San Diego State University, he was “kind of lost, wondering what he was doing there. Basically, he found a way to commit himself to his community. So I think when you see this film, especially the young people in this audience, think about yourself, think about the choices Chunky had to make – very similar to some of the choices you all have to make today – thinking about how Chunky was going to make a commitment to his community over time.

“And I think one of the things that really inspired me to make this film was the great, great dedication that I saw in Chunky. I knew him for many, many years, and it was something I wanted to bring to a much larger audience.”

During a 30-minute discussion after the film, led by Enrique Murillo Jr., CSUSB professor of education and founder and executive director of the Latino Education and Advocacy Days project, an audience member asked what message Espinosa hoped to impart. Instead, he asked the audience what they thought the film’s message was.

The responses ranged from to be proud, to be who you are and not to be afraid to stand up for yourself, to stand up for your rights. “We live in a culture that does put down people who are different,” Espinosa said. “And I think, certainly, one of the things that Chunky always believed was to be yourself, and be proud of who you are.”

Earlier, Murillo said, “Chunky’s music made us more Chicano … He basically made it easier to be Chicano. He made it easier to be who we are.”

Said Espinosa, “Chunky was one of these people, through his art, to focus on the idea of being bi-cultural, bilingual, and having a foot in two different worlds. That’s the world that he grew up in, and that’s the world he felt that he wanted to present to other generations.”

He pointed out that one of Sanchez’s signature songs was “Pocho,” about being of Mexican heritage, yet not being fully Mexican, and being born and raised in the United States, yet not considered fully American (as it was defined then).

As he has shown the film throughout the country, Espinosa said he has seen that many people identified with that notion as well, “not just Mexican-American, but there are lots of people who are basically newly arrived in this country from different places … and find themselves in this dilemma of basically being pressured to sort of become American without fully understanding what becoming American really means.”

Charlene Eaton, who teaches a class on race and racism at CSUSB, brought her students to the screening. One student said that she has learned so much about herself and her culture during the fall quarter in the class, and the film illuminated that even more.

Espinosa said that her response about learning more about her history and culture was one he experienced frequently at screenings. For example, the film showed the building of San Diego’s iconic Chicano Park, in which Sanchez played a part, and a young woman who had always lived near there never knew the history behind it.

That was a large failure on the part of the education system, particularly in the high school level, Espinosa said. For many students, it’s not until college that they learn of the historical role minority communities played in various places, he said.

Hispanic Heritage Week was established by legislation sponsored by Rep. Edward R. Roybal (D-Los Angeles) and signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson in 1968. The commemorative week was expanded by legislation sponsored by Rep. Esteban Edward Torres (D-Pico Rivera) and implemented by President Ronald Reagan in 1988 to cover a 30-day period (Sept. 15-Oct. 15). The bill died in committee, but in 1988, Sen. Paul Simon of Illinois re-submitted an amended version of the bill, which was enacted into law on Aug. 17, 1988.

Sept. 15 of every year was chosen as the starting point for the celebration because it is the anniversary of independence of five Latin American countries: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua, who all declared independence in 1821. In addition, Mexico, Chile and Belize celebrate their independence days on Sept. 16, Sept. 18 and Sept. 21, respectively.

For more information, visit the Hispanic Heritage Month website or the CSUSB HSI Events webpage.