Joe Gutierrez | CSUSB Office of Strategic Communication | (909) 537-5007 | joeg@csusb.edu

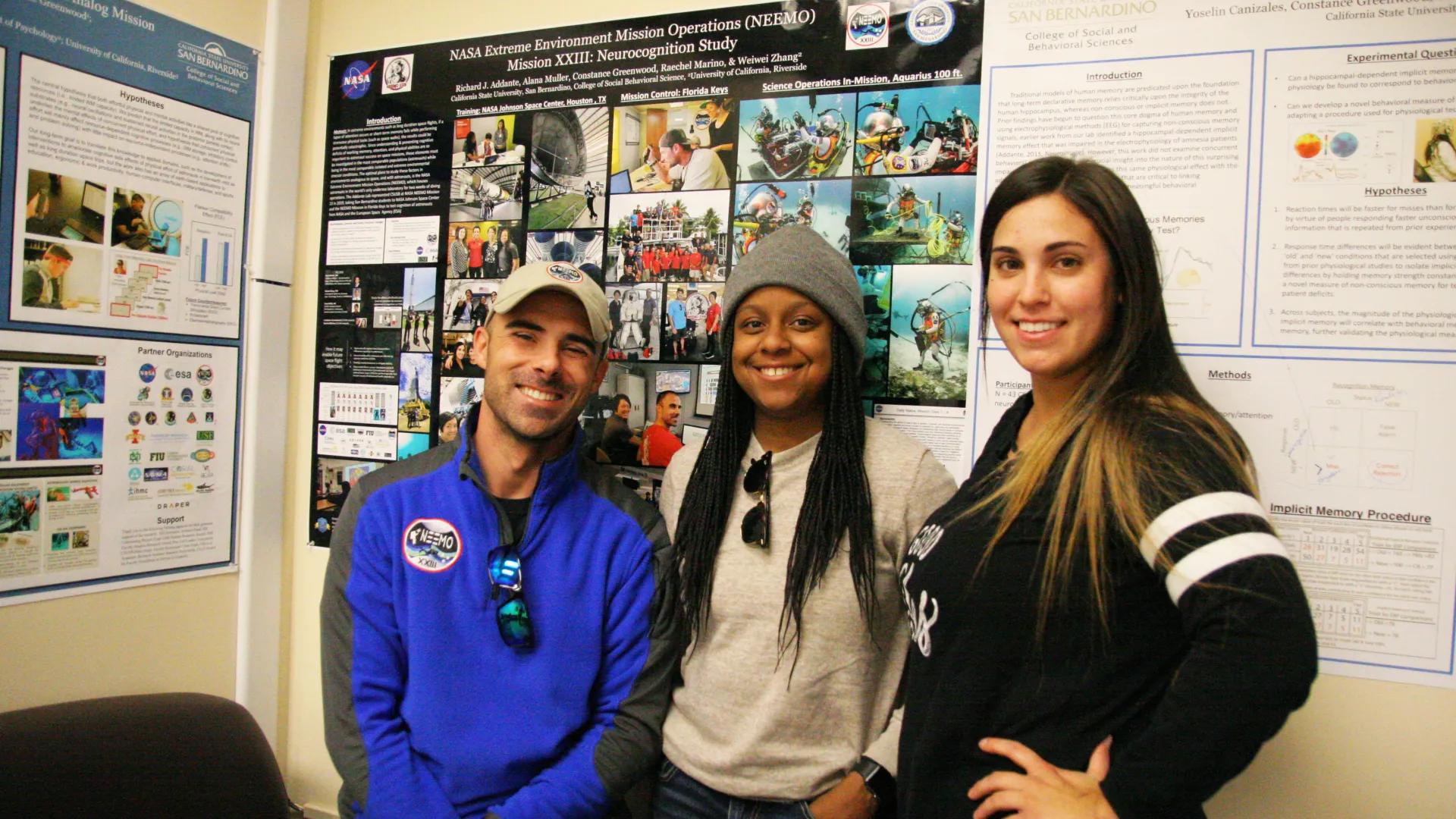

At the end of their junior year in May 2019, Cal State San Bernardino psychology students Constance Greenwood and Raechel Marino traveled to Houston, Texas, and faced a room full of astronauts and a contingent of scientists from NASA and around the world to teach them how to run their experiment to measure brain activity for an upcoming mission.

“I get really nervous speaking in front of people and presenting things like that,” said Marino, who graduates in June, as will Greenwood. But their Johnson Space Center audience – with its highly accomplished members – was “really humble and they all made us feel like we belonged, even though we were undergrads.”

While it may have been nerve-wracking at the start, it didn’t end that way. As Richard Addante, their psychology professor on the project, explained it, “They did a great job. I was telling them that after I introduced the project, one of my favorite parts was I got to just stand back and watch them take the reins to do what they were trained to do. … And it was perfectly executed.”

Sit with Greenwood, Marino and Addante to hear how they got to that point, and it’s a journey of hard work, of having the mindset of test pilots, and knowing that their research will have an impact in space exploration. And while it revolves around the development of a mobile EEG device that would monitor the brain activity of astronauts in space, like many NASA innovations (think of Velcro), there are spinoff benefits, not just for the students, but the university as well.

But it’s best to start at the beginning, when Addante was a crew member with the 14th Human Exploration Research Analog, or HERA, in August 2017 at the Johnson Space Center. HERA 14 simulated a long duration space mission of 45 days, but was cut short when Hurricane Harvey struck Houston. Despite the truncated mission, participating in HERA demonstrated to NASA that having someone with a neuroscience/psychology background on the crew had advantages, and helped him forge a working relationship with the space agency.

“It’s like having a doctor there, but a doctor who understands the cognition of the mind,” Addante said. A long-duration space mission is “by the potentially lonely, depressing and there will likely be interpersonal issues to address … and all this happening in a place far from home, and where the option of leaving (as there is on Earth) is not available. And there’s not a pill or medication you can take to solve some of those problems.”

So, understanding how people would react and adapt to the challenges of being confined in a relatively small spaceship during a mission to Mars becomes more important. “We’re on the cusp to lead to innovations for space travel on the human side,” he said. “We’re definitely taking that idea of test pilots of the human mind forward.”

Part of the research at the CSUSB Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory in the Department of Psychology is the development of a mobile EEG device that would measure the brain activity of an astronaut during a mission as a potential countermeasure for cognitive deficits that could become catastrophic on future missions to Mars. The chance to further develop it came when the lab had an opportunity to come up with something that could be used on NASA’s NEEMO 23 mission (the name comes from “NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations”) an underwater analog that aims to simulate a space mission by having astronauts perform the kind of tasks as they would in space while living in a small capsule at the bottom of the ocean, about 60 feet below the surface.

Developing the experiment for NEEMO 23 took about a year and a half, Addante said.

“There was a lot we had to do here to prepare for that, Greenwood said. “Long nights here (at the lab at CSUSB), leaving the lab at 4 in the morning, making sure we had an experiment that ran at a steady pace, and it did. We really proved ourselves during that baseline testing. We were able to run through it with zero problems. It was nice to see all of that hard work – all the long nights that we spent together as a team – pay off.”

In May, the three of them and Alana Muller, then a CSUSB master’s student in the Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory who has since gone on to the Ph.D. program at the University of Arizona, traveled to Houston to present their research and show the astronauts and scientists how to implement it during the NEEMO mission.

Though Greenwood and Marino may have been in awe of the people they were presenting to, in the end, they were just as impressed with the students, if not more so.

“They talked to us like they talked to anybody else,” Greenwood said. “They really were interested in know our experience as undergrads. I think we were the only undergrads there. That was really unique. Shirley Pomponi (a research professor at Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute-Florida Atlantic University and professor of Marine Biotechnology at Wageningen University) who was a scientist on the NEEMO mission said to us, ‘You guys are undergrads. What are you doing here? I’ve been waiting forever to get here.’”

They were further taken into the fold at a social gathering. Greenwood said they were hesitant to approach anyone. Yet, “There were, all throughout the night, people who would approach us and just say, ‘Tell us about your study,’” she said. “You think that being in this situation everybody knows everything about everything that’s going on. But that’s not the case. There are people who are specialists who know nothing about the psychological elements that we were bringing to the table. That was really nice of people to come to us and ask us about the experiment, the design, what we’re trying to achieve. And vice-versa: We were able to get their feedback, too.”

“And they did not treat us as undergrads at all,” Marino said. “They treated us as if we were any researcher there.”

“They were treated that way because they demonstrated they were competent, they knew what they were doing, and they were professional,” Addante said. “That’s what we train for here. We spent all year basically getting ready for that experience so that both sides of that equation fit. They would be treated that way because they acted like colleagues, graduate students and scientists.”

The students also drew inspiration from the four-member NEEMO 23 crew, which was all women.

“I’ve never seen women who are highlighted in science, let alone women of color,” Greenwood said. “It was really special to have conversations with (NASA astronaut) Jessica Watkins, seeing someone I can relate to being in this field, trying to chase some of the same goals and contributing.”

There was, though, one non-scientific exchange of ideas. Samantha Cristoforetti, an astronaut with the European Space Agency who was commander of NEEMO 23, became intrigued with the circular devices attached to the students’ smart phones – PopSockets – that make it easier to hold the phones with one hand. Seeing that it could be useful for all the photo ops and selfies she takes as an astronaut for ESA, (and perhaps, on the International Space Station the next time she goes up), she inquired about them, and the students gave her three to use with her smart phone.

“There is so much behind these four walls happens on a day-to-day basis that are incredible things,” Greenwood said. “I know that we’re not like an R1 school (a top-tier research institution) but we’re doing R1 activities, and we’re doing experiments that are impactful. These (pointing to the research posters on the wall of the lab) are never going to die. These experiences are never going to die. So, I think that’s really special.”

And it was on a foundation laid by the students and him. Work continued on the mobile EEG through the fall 2019 and winter 2020 quarters (before the COVID-19 stay-at-home orders) with Greenwood, Marino and others from the CSUSB lab taking to the skies as Addante piloted a small plane.

All the work by Greenwood and Marino is a continuation of what was started by Muller and alumna Lindsey Sirianni, who now works for NASA in the Behavioral Health & Performance Lab, Addante said. And Greenwood and fellow lab student Rosie Valencia were invited to go on an all-expenses-paid trip to visit the neuroscience doctoral program at UC Davis, the Neuroscience Initiative to Enhance Diversity, where they received several days of tailored mentoring for applying to Ph.D. programs, following in the footsteps of CSUSB lab alumna Rose DeKock, who also went through that program and is now in her third year as a doctoral student at UC Davis.

Addante also was invited to present at the NASA Human Research Program Investigators Workshop in Galveston, Texas, in late January, where he gave a talk on the “Crew Perspective of Psychology Research in Analog Studies of Long Duration Space Flight.”

Through their work, the perception of CSUSB by those outside the university has changed.

“I think that’s part of the direction (CSUSB) President Tomas Morales is trying to lead us in, to redefine the expectations of what we are,” Addante said. “What we try to do in the lab is exceed expectations, because we redefine our standards of what is normal and what is expected. That’s what we’re doing. They (the students) are leading the way in that.

“Lindsey and Alana led the way, and Raechel and Constance are following,” he said. “We’re changing the standards of what people think CSUSB is.”

One example of how that’s changing is how people referred to the CSUSB, taking the “SB” to mean another campus in another state university system, when they first started working on the NEEMO mission, Addante said.

“But by the end of the mission, and certainly by the time they invited us to go on the NXT mission with the ExoSuit, they weren’t making that mistake anymore – they would say the name correctly, they knew what it meant and they respected what it meant because we changed those expectations and redefined that standard.”