Joe Gutierrez | Office of Strategic Communication | (909) 537-5007 | joeg@csusb.edu

Kimberley Cousins, professor of chemistry and chair of the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, has risen steadily through the academic ranks, earning recognition for her extensive list of accomplishments every step of the way. She joined Cal State Bernardino in 1991 as an assistant professor, was named associate professor in 1997, became a full professor in 2004 and was named department chair in 2017.

She received CSUSB’s top teaching award, the Golden Apple for Excellence in Teaching Award in 2008, and was named the university’s 2019-20 Outstanding Professor.

She has served as a leader through her involvement in the Faculty Senate and the CSUSB Teaching Academy, and serves on numerous departmental retention, promotion and tenure committees both in and outside her department.

During her career, she has written or co-authored proposals that have been awarded nearly $20 million in funding from public and private agencies, the majority of which has been to ensure that low-income, underrepresented minorities have opportunities to enter STEM fields.

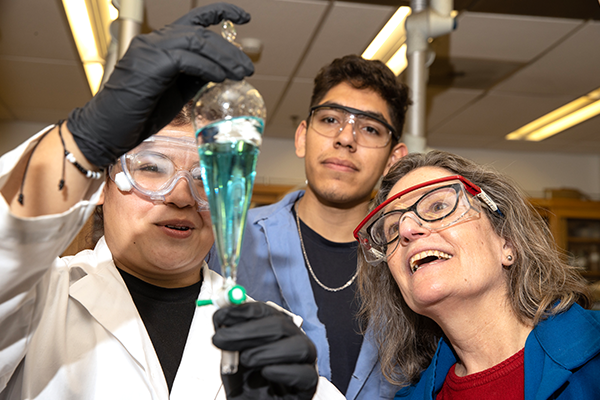

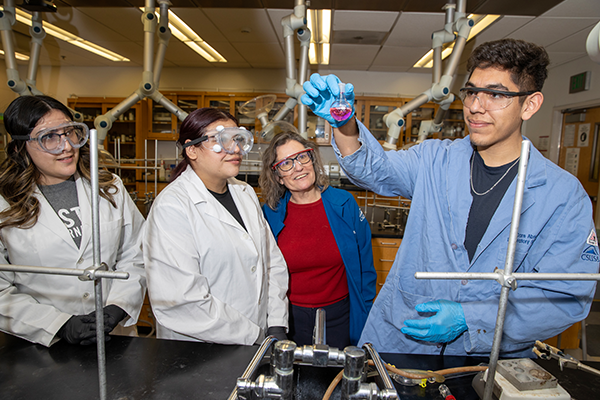

When asked what motivates her, the answer is simple. “Our students,” she says. “Our students are great. To see where they come from and what they overcome to get here, to be here. It’s just absolutely amazing.”

And Cousins has dedicated herself to ensuring that once students are here, they have the resources, support and opportunities needed for success in the STEM fields.

Cousins is the principal or co-investigator for several multi-million-dollar grants from the National Science Foundation for the S-STEM program (“Scholarships in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics), and has served as director of the program since 2011.

With a focus on academically talented but financially needy students, the purpose of the program is to graduate well-prepared candidates for employment in STEM fields or for graduate study in STEM disciplines. Each student receives scholarship support; faculty mentorship; cohort-specific academic support services; and co-curricular activities to develop as scientists, mathematicians, engineers and STEM teachers, including opportunities to participate in STEM research.

The results of the program have been highly successful, and to date, more than 250 students from financially disadvantaged, underrepresented groups have graduated to become STEM leaders in the region. Of the 50 CSUSB graduates from the current grant, more than one-third are advancing to pursue graduate degrees or teaching credentials, and more than 60 percent are employed in STEM industries, primarily in the Inland Empire.

Cousins is also the principal investigator for the Centers of Research Excellence in Science and Technology II (CREST II) program, the second $5 million NSF grant awarded to the college’s Center for Advanced Functional Materials (CAFM). (She was co-investigator for the first $5 million NSF awarded to the program.) The funds help broaden CSUSB’s capacity to recruit and retain diverse students pursing STEM degrees and careers, as well as strengthen research collaborations with institutions and local community colleges to help students advance through the academic pipeline.

The success of the CREST I program can be seen in the data: 110 CSUSB students, 138 community college students, and 25 high school students enrolled in the program. Fifty-seven percent of the undergraduates identified as Hispanic and 53 percent as first-generation. Out of 53 CAFM graduates, 29 enrolled in STEM programs at graduate schools across the country. Data for the CREST II program are not yet available, Cousins said.

The Critical Importance of Diversity in STEM Fields

Recruiting women, low-income and people of color to STEM professions is of critical importance for several reasons, says Cousins. “First, STEM fields have low unemployment, good incomes and job security,” she explains. “So, that’s a plus.”

And heightening awareness of the myriad opportunities that exist in the STEM fields is crucial. “One of the roadblocks we run into is that a lot of young girls and first-generation students of any identity don’t understand the kinds of professions that are available,” she said. “Oftentimes, students and their families think the career possibilities in STEM are limited to teaching science or becoming a doctor or a nurse, which isn’t true.”

More importantly, recruiting people of color to STEM professions is essential to creating a robust pipeline of mentors for future generations. Currently, Cousins said, the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry is comprised primarily of white and East Asian faculty members, “yet our students are 15 percent white and East Asian, and 85 percent other ethnicities. (As a student), it’s really helpful to see someone who has walked your path.”

“Bringing in people with different perspectives and different ways of solving scientific problems is what we need,” she adds. “We need people who think outside of the box, and one of the ways to get that kind of rich thinking is to bring people from different backgrounds.”

And as the parent of a 23-year-old and a 27-year-old, Cousins recalls alluding to the children’s character Bob the Builder and concoctions such as slime during classes when her children were young. “I have had students over the years — when I’d make references depending on my kids’ age — say, ‘I can’t believe you’re a mom and you’re an organic chemistry professor.’ And I’d say, ‘Well, you can’t do everything at the same time. But you can do them all within your lifetime.”

At this stage in her academic lifetime, Cousins plans to serve as department chair through the end of the 2023 academic year. After that, she says, “I’m super excited about returning to have more time to spend with my research students.

“Mentoring students is really the basis of all of this. That’s what keeps me going,” she says. “It’s having students, in wherever stage they happen to be, and watching their growth. It’s watching a student walk in and say, ‘There’s no way I can do this research. It’s just too specialized. I can’t possibly do it.’ And then seeing them a year later at a conference, presenting a poster or a paper on that very topic.”