Joe Gutierrez | CSUSB Office of Strategic Communication | (951) 236-4522 | joeg@csusb.edu

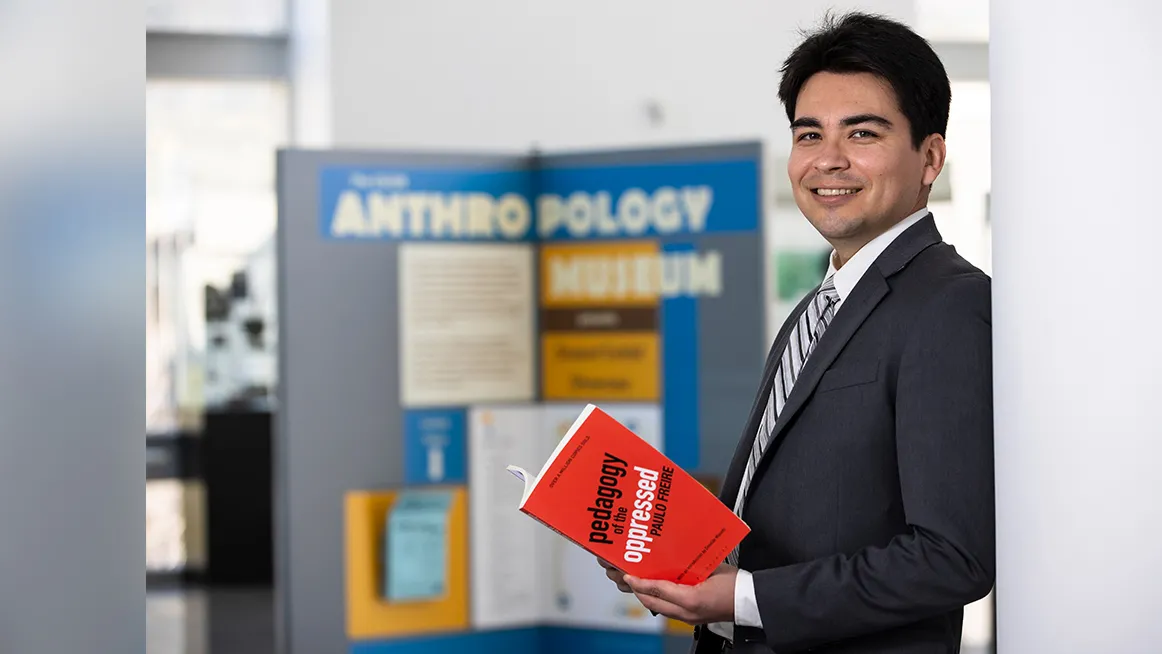

Consent, consensus and collaboration – the three principles Danny Sosa Aguilar follows when conducting his archaeological research. And with these three important practices, the Cal State San Bernardino assistant professor of anthropology is able to “research with empathy.”

“Archaeology has always had a bad history with indigenous people,” Sosa Aguilar explains, whose research is steeped in the practices collectively known as indigenous archaeology. “So what indigenous archaeology does is it tries to center the people whose history you study and the descendants of those people into the project itself.”

In other words, archaeology has a history of taking artifacts and putting them in museums without ever giving a voice to indigenous communities; indigenous archaeology is designed for, by and with indigenous people. And by applying the three important principles – consent, consensus and collaboration – the hope is to generate a mutually beneficial project.

According to Sosa Aguilar, after gaining the consent of community leaders, it is then important to seek community consensus by attending events that are open to the public, speaking to people about the work you do, and any other task necessary to get an understanding for what the community feels. From there, collaboration begins.

“It’s all the previous groundwork that really establishes the basis for a real collaborative and making the archaeology indigenous,” says Sosa Aguilar, who also serves as a member of the Presidential Advisory Committee for the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, formed as a way to engage in meaningful consultation with Native American tribes and repatriation of sacred objects.

For his Abiquiu Mesa Project in New Mexico, which started with his dissertation at UC Berkeley, Sosa Aguilar, community partners and Abiquiu community members work together to find out more about their history, give back that history to the community and make sure it is something that goes into the next generation.

“Through archaeology and the oral histories of the Abiquiu community, we build that knowledge and hope that it stays within the community and they can continue to grow it,” he says. “We’re producing academic knowledge, but also giving back that information to the community, having them decide how they want to use that knowledge, and also making sure that they are involved in the process and giving them a voice in the building of the historical knowledge.”

While working at UC Berkeley, Sosa Aguilar would take undergraduate students to New Mexico and work in the field. Through a grant from the nonprofit organization El Pueblo de Abiquiu Library and Cultural Center, the group would help and work with Abiquiu youth from 8th to 12th grade.

“Not only are students learning about their history within their own land, but also participating and getting paid for it,” Sosa Aguilar says. “In a sense, they’re interns because they are learning how to do archaeology and learning about the history.”

The idea is to create a tiered mentorship program where the college students mentor the high school students, while Sosa Aguilar mentors the undergraduates and the local youth. Sosa Aguilar, who came to CSUSB this 2021-22 academic year, is working to implement this structure again, but next time, with CSUSB undergraduates and graduates – a student body he knew he wanted to work with.

“This is a student body I can teach,” he thought when applying for his faculty role. A lot of his teaching style, he says, has been influenced by his experience as a first-generation student – more than 80 percent of CSUSB students identify as first-generation.

“I have a lot of knowledge that I gained from going through grad school and undergrad, and I struggled a lot. I have knowledge that I can share and really give back. I can help out and be a mentor like those who were mentors for me,” he says.

And just as he researches with empathy, Sosa Aguilar also teaches with it.

“I empathize by understanding how students feel in the process and allowing them to feel empathetic toward each other through various group projects,” he says, noting that his classroom is more about participation than tests.

“I tailor my classroom in a way that caters to what I would have liked in my undergraduate work,” he says. By basing his class more on participation, “it gives students the opportunity to really show themselves as who they are, and they learn more through discussion than simply memorizing material and then forgetting about it the next day.”

Sosa Aguilar not only hopes to pass on empathy to his students, but also critical thinking, something he calls “essential.”

“I want to get people to think about the past differently,” he explains. “I want them thinking how people in the past were human, that they have descendants, and to think critically of how the past actually influences the present and ultimately plays a big part in our future.”

By thinking of the past in this way, Sosa Aguilar says students then begin to see a lot of connections to present day, like systemic problems and disparity.

And as he finishes his first academic year at CSUSB, Sosa Aguilar hopes to continue to teach his current and future students these kinds of connections and the importance of empathy.

“I’m finally in a position where I can give back,” he says. “I chose CSUSB because of the student body and I hope to stay in this community. I can really make something within this community.”