Joe Gutierrez | CSUSB Office of Strategic Communication | (951) 236-4522| joeg@csusb.edu

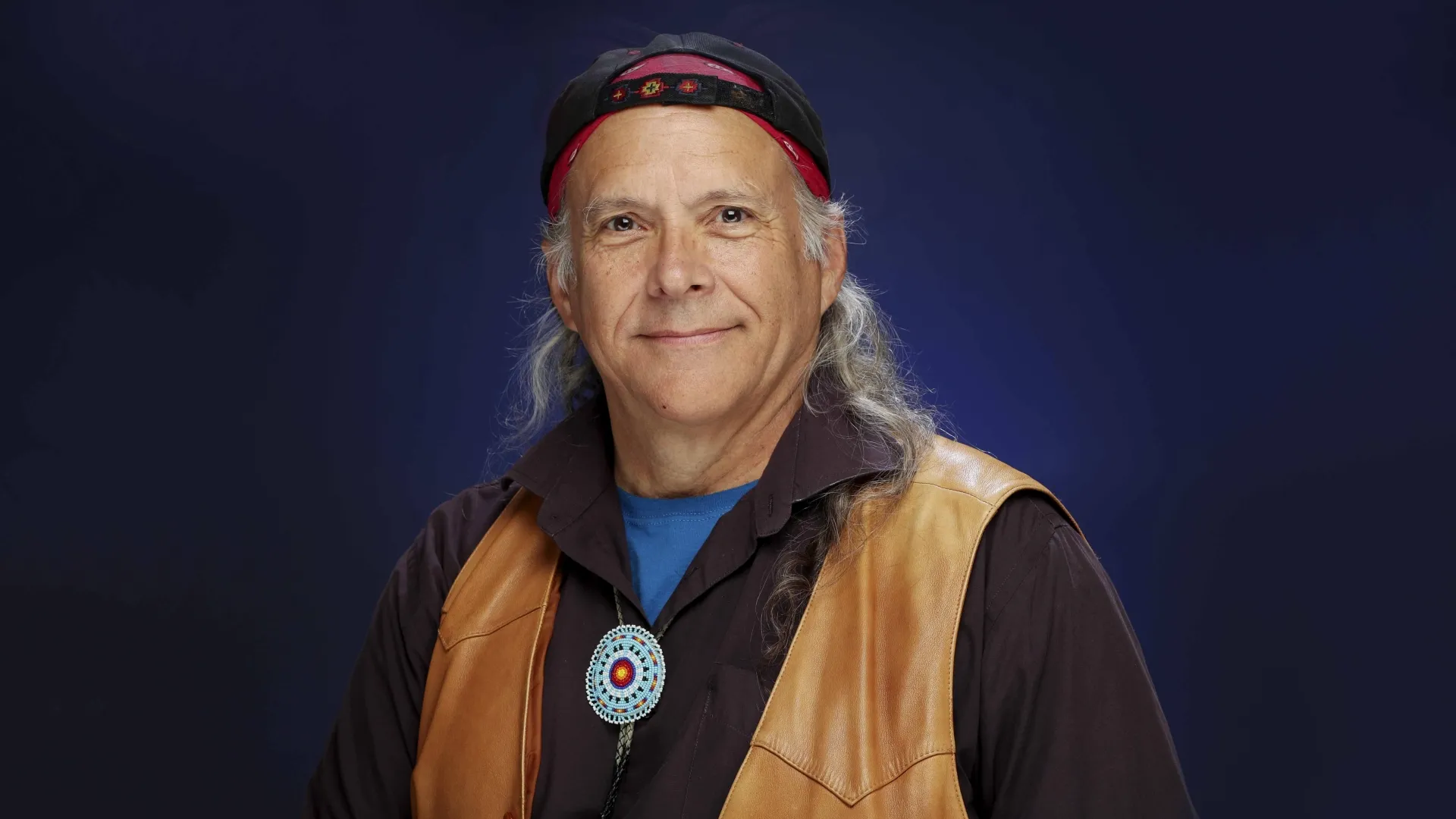

Through his writings and his work with the Native American community, James Fenelon, CSUSB professor of sociology and director of the university’s Center for Indigenous Peoples Studies, is an advocate for social justice around the world.

“Social justice, when delivered nationally or globally, is linked to peoples and nations and ethno-racial groups who work for a better more just world for themselves and others,” said Fenelon, who is Lakota/Dakota from Standing Rock (Nation). “Usually this means they are progressing out of colonialism and domination, often in social movements linked to international organizations and structures with justice and equity for all peoples.”

Fenelon notes that with the United Nations and Native people, this was realized with the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which “took 30 years of such struggle to get accepted and now many nations, tribes and peoples are looking to be realized in their respective governments.”

Fenelon, whose areas of teaching include urban inequality, social movements, Native Nations, and race and racism, has also examined and written about the negative representation of Native Americans in professional sports and the effects it has had on the Native community.

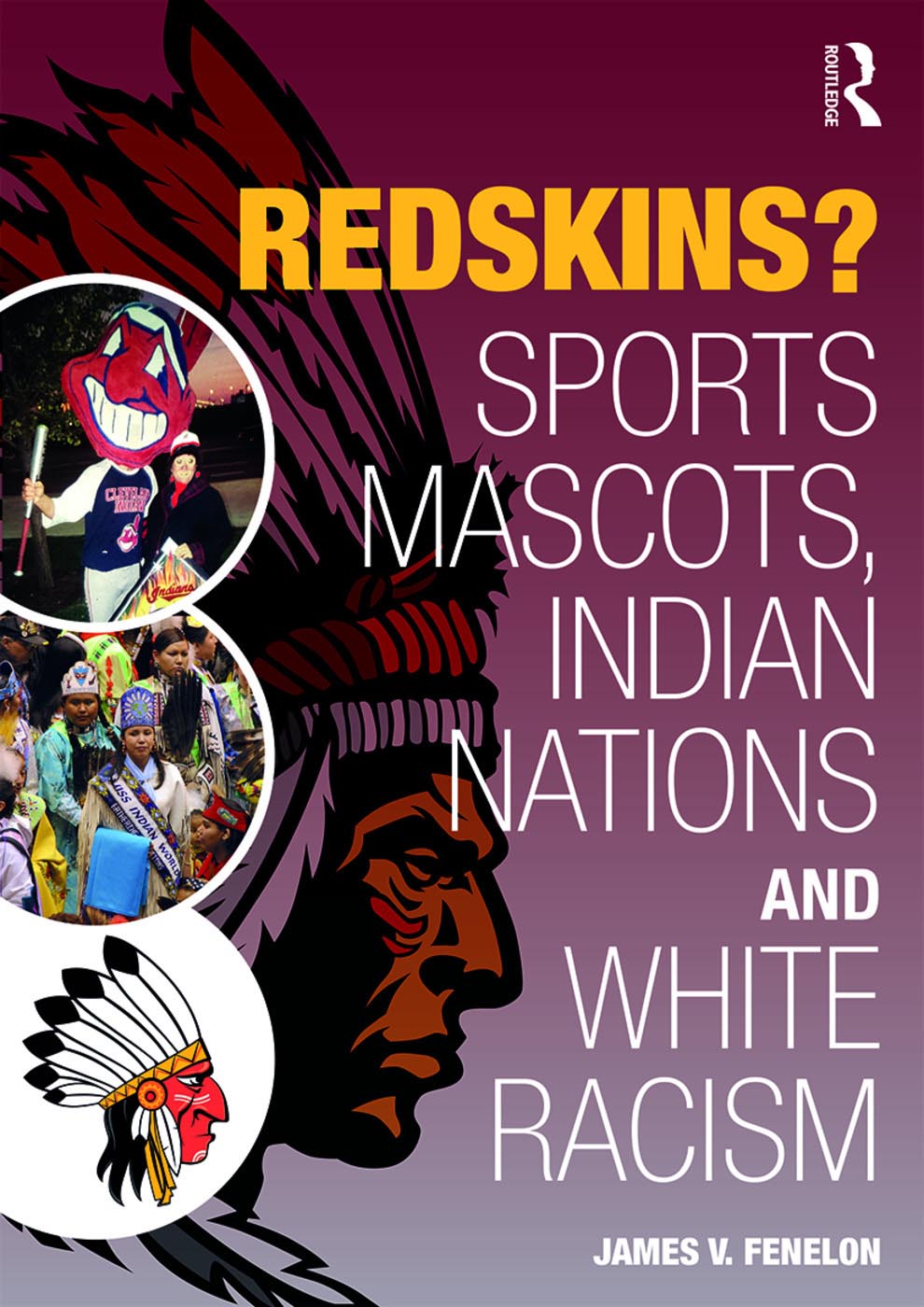

In his 2016 book, titled “Redskins? Sports Mascots, Indian Nations and White Racism,” Fenelon addresses compelling social issues concerning Native Nations cultural sovereignty and representation. Specifically, according to its description, the book “assesses the controversies over the Washington NFL team name as a window into other recent debates about the use of Native American mascots for professional and college sports teams” and “explores the origin of team names in institutional racism and mainstream society’s denial of the impact of four centuries of colonial conquest.”

“These issues are of great importance to Native leaders and nations, since they are more than symbols, but represent how our Nations and peoples are considered by the dominant society, historically and in contemporary ways,” Fenelon said. “And they are linked to the kind of racism that we see in conflict all across our nation now.”

Fenelon, who has taught internationally with indigenous peoples globally and with urban groups, decided to write the book after Joe Feagin, one of the nation’s leading scholars on white racism, had asked him to consider doing so. Fenelon had also conducted studies in Cleveland and in California on the Major League Baseball team the Cleveland Indians with their mascot Chief Wahoo, as well as surveys on the Washington NFL football team, which dropped the Redskins name before the 2020 season began.

“They are considered the most offensive mascot and team name in professional sports,” Fenelon said. “I was the first to systematically find Native peoples were deeply offended, which went against mainstream accounts and surveys, collected without knowledge of Indigenous communities and issues.”

In July 2020, the Washington NFL team confirmed their name change to the Washington Football Team, after pressure from sponsors and Native American groups who have argued that both the team name and main logo are racist. Although the new team name is not final, what is definitive is the name “Redskins” has been permanently retired.

“It’s about time the team did so, but it is way, way too late, since a primary reason is that the icons, statues and racist stereotypes of racial-ethnic minorities is now in full frontal exposition to the American public, thus the team owners were losing support from the fanbase, players and general academia,” Fenelon said. “It’s interesting to note how long they held out, being the last team in the nation to give up racial exclusion of Blacks on their teams, often with neo-Nazi support. Now, we want to see deeper kinds of taking responsibilities to repair the imagery and relations that have experienced such negative effects for so long.”

Fenelon’s other book, “Indigenous Peoples and Globalization” (with Thomas D. Hall), reflects current research writing, combining American Indian struggles for sovereignty and representation, which builds from his first book, “Culturicide, Resistance and Survival of the Lakota (Sioux Nation).”

He has also published numerous articles and book chapters, including publications on indigenous peoples and genocide in California for the academic journal “American Behavioral Scientist,” and on climate change wars and indigenous peoples for “Political Economy of the World-System” research volumes and “World-Systems Analysis in the Anthropocene” in the Journal of World-Systems Research.

Fenelon has also worked with the Urban Conservation Corps, the California Indian Nations College, and worked on environmental water research with the Water Resources Policy Institute for the California State University.

And as the director of the university’s Center for Indigenous Peoples Studies (CIPS), Fenelon further supports “the most underserved of all peoples in United States colleges and universities – the Native.”

CIPS was started with the support of former College of Social and Behavioral Sciences Dean Jamal Nassar, who observed the lack of Native Nations, American Indians and indigenous peoples programming on campus. Since its inception, Fenelon has taken the center to a more academic and globally oriented level. CIPS is now the primary site for innovative programs for the study of American Indians and local, national and international indigenous peoples.

To learn more, visit the Center for Indigenous Peoples Studies website.